Who?

Anne

Where?

Istanbul, Turkey

What?

"This was a wonderful statement right there."

How did she react?

"Thanks. It's just what I observed."

How did I feel?

Two girls, four hours of strolling through Istanbul, seven hills to climb to the sea, and hundreds of waves coming in at the shore. Totaled up this equals: A conversation about everything. Everything. From life to death. From love to hate. From women to men -- and everything in between. In the case of the latter, literally:

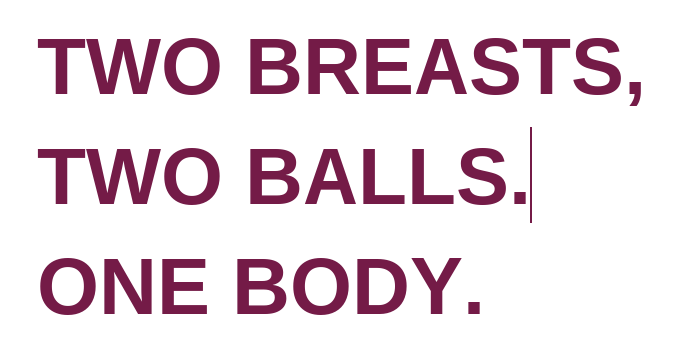

Anne studies art in Istanbul for one semester. At one point in our chat she told me about a life drawing course in which the current model is a transsexual. The person has (female) breasts and a penis. She has been posing for the class repeatedly. I asked her, "What is it like drawing her or him? For you, I mean?" She remained silent for a moment. Then she said, "It changed over time. I remember when she - I think she considers herself a she - first posed I kept analyzing her body as I was drawing. I would look at her from different angles, thinking "Huh, this is a male feature." Or, "This, right there, looks pretty female." But now, a few sessions later, these thoughts don't come up anymore. I just look at her and go like, "This is a beautiful body." "

This is a beautiful body. No more, no less. I smiled and nodded. Anne's words came honestly and spontaneously. They were no planned speech nor politically correct rambling. She merely shared her experience. At the same time those three sentences were some of the wisest I had ever heard.

We have all been there: Put us in a new situation and we will start labeling. Female or male, big or small, beautiful or ugly, black or white, Jewish or Muslim, single or married, West Coast or East Coast, John Lennon or Paul McCartney. Right or wrong.

Now I am not saying this is a bad thing in itself. Labeling things structures our environment. It helps us orientate in complex surroundings, decreases our feeling overwhelmed, even saves our lives sometimes: If you label the flames from your car as "dangerous" that might be helpful right there. Labeling is a means to survival. I believe it belongs in the same wonderful toolbox that contains fear, aggression, hate, anger, stubbornness and insecurity. The box with its instruments helps us realize our boundaries and stay within them. It reminds us who we are and teaches us about where we come from. But if we blindly use those instruments all the time we miss out. When and how to use which tool from the life savior box, and when not to use one at all, is maybe the most valuable lesson to learn.

To me Anne's story sounded like she had been bringing tools to her class. A ruler, maybe the triangle, too. Measuring and categorizing the model she had not only gauged her proportions, but also the quality of her features. One of her rulers' scales had divided "male" and "female". For a few weeks she had spent the class classifying the body in front of her. Until one day, without Anne noticing, she had left the male/female ruler inside the toolbox. It had become superfluous. At this point she had labeled the model often enough. That day, because she was not busy measuring anymore, she had started enjoying the view. "Now I just look at her and think, what a beautiful body."

My favorite part about Anne's words: She was not giving me shit. Anyone can say "It don't matter if you're black or white." or "Transsexual? Why not?" without ever having been in touch with a transsexual or someone facing similar problems in society- just through understanding that it is logical to support Black Lives Matter or LGBT rights. And sure, having an open mindset is a good thing to start with. But a pluralistic attitude is not the same as personal experience. Being in touch with someone or something new, going through irritation, resistance, measuring, fear of the unknown and being honest about that will lead to a different way of embarking on the person or the surrounding. There is a different depth to a statement like "What a beautiful body" after a process that includes being weirded out. Anne's story illustrated that rather than proclaiming tolerance and openness admitting irritation and judgement to oneself and others can open up a whole different dimension of insight and growth- if there is time and space to encounter that which is new and overwhelming. Be it a look, a person, a place, a feeling or a state. Oftentimes admitting these sensations requires trust. Not just trust in the process but also trust in yourself and your interlocutor. Again, because of a label: Being irritated is not cool. For who likes to admit they are weirded out at the sight of a penis that comes with a pair of boobs dangling above it, in 2015? Saying that out loud will cause at least one disgusted look, one "Go back to the fifties!" or one "You are an ignorant asshole!". But you are not. Admitting and walking through irritation, making use of the tools in your box like the male/female ruler, allowing yourself to do that, reminds me of WIttgenstein's ladder. The one you throw away after you have climbed it. Eventually you let the ladder go but you can't move upwards without the ladder. And you can't put the "male"/"female" ruler back into the toolbox unless you have picked it up before. Applying it does not mean claiming that its measurements, or any other of the toolbox's realities, equal the absolute truth. It does not mean going around and saying, "See, here she is female. Here she is male. And this part, aw well, hard to say. It kinda does not look human at all. Right?" But it means experiencing those thoughts awarely and allowing the thoughts to be (part of) your momentary truth. The same way that every new segment of a ladder you are climbing is your momentary truth. It means giving in to the process the way Anne did. Even if what you are experiencing seems wrong, bad, or evil. Be it thoughts, emotions, or ideas. And finally, it means trusting in that process even though you don't know what waits for you at the end.

I used to work for a professor who made a huge deal of being a feminist. At the same time he loved himself his hierarchies and made sure none of us female assistants questioned any of his claims and attitudes. But in theory he was a full on feminist. He would call in male staff to serve coffee at conferences so his guests would not assume he let women do the low skilled tasks (although all the secretaries and assistants at the institute were women while the people of high positions were men, without exception). That night, sipping bitter-sweet black tea by the sea with Anne, I thought of that former professor of mine. And I realized: I had learned more about feminism from Anne's life-drawing story about being real, even if that means going through "incorrect" stages, than from 1.5 years of working for the man with the polished feminist arguments.

I admire the way Anne gave in, allowed, trusted, and shared her experience with me. Her curiosity, acceptance and overall perspective were gifts to me. In the two weeks since we have met I have thought of her each time I felt irritated, and while I tried to immerse in the irritation it did not translate to my face because the memory of Anne occupied my mouth, causing my broadest smile.

The next morning, as I headed to the airport, I took pictures of the hills Anne and I had climbed on our way to the sea:

Anne

Where?

Istanbul, Turkey

What?

"This was a wonderful statement right there."

How did she react?

"Thanks. It's just what I observed."

How did I feel?

Two girls, four hours of strolling through Istanbul, seven hills to climb to the sea, and hundreds of waves coming in at the shore. Totaled up this equals: A conversation about everything. Everything. From life to death. From love to hate. From women to men -- and everything in between. In the case of the latter, literally:

Anne studies art in Istanbul for one semester. At one point in our chat she told me about a life drawing course in which the current model is a transsexual. The person has (female) breasts and a penis. She has been posing for the class repeatedly. I asked her, "What is it like drawing her or him? For you, I mean?" She remained silent for a moment. Then she said, "It changed over time. I remember when she - I think she considers herself a she - first posed I kept analyzing her body as I was drawing. I would look at her from different angles, thinking "Huh, this is a male feature." Or, "This, right there, looks pretty female." But now, a few sessions later, these thoughts don't come up anymore. I just look at her and go like, "This is a beautiful body." "

This is a beautiful body. No more, no less. I smiled and nodded. Anne's words came honestly and spontaneously. They were no planned speech nor politically correct rambling. She merely shared her experience. At the same time those three sentences were some of the wisest I had ever heard.

We have all been there: Put us in a new situation and we will start labeling. Female or male, big or small, beautiful or ugly, black or white, Jewish or Muslim, single or married, West Coast or East Coast, John Lennon or Paul McCartney. Right or wrong.

Now I am not saying this is a bad thing in itself. Labeling things structures our environment. It helps us orientate in complex surroundings, decreases our feeling overwhelmed, even saves our lives sometimes: If you label the flames from your car as "dangerous" that might be helpful right there. Labeling is a means to survival. I believe it belongs in the same wonderful toolbox that contains fear, aggression, hate, anger, stubbornness and insecurity. The box with its instruments helps us realize our boundaries and stay within them. It reminds us who we are and teaches us about where we come from. But if we blindly use those instruments all the time we miss out. When and how to use which tool from the life savior box, and when not to use one at all, is maybe the most valuable lesson to learn.

To me Anne's story sounded like she had been bringing tools to her class. A ruler, maybe the triangle, too. Measuring and categorizing the model she had not only gauged her proportions, but also the quality of her features. One of her rulers' scales had divided "male" and "female". For a few weeks she had spent the class classifying the body in front of her. Until one day, without Anne noticing, she had left the male/female ruler inside the toolbox. It had become superfluous. At this point she had labeled the model often enough. That day, because she was not busy measuring anymore, she had started enjoying the view. "Now I just look at her and think, what a beautiful body."

My favorite part about Anne's words: She was not giving me shit. Anyone can say "It don't matter if you're black or white." or "Transsexual? Why not?" without ever having been in touch with a transsexual or someone facing similar problems in society- just through understanding that it is logical to support Black Lives Matter or LGBT rights. And sure, having an open mindset is a good thing to start with. But a pluralistic attitude is not the same as personal experience. Being in touch with someone or something new, going through irritation, resistance, measuring, fear of the unknown and being honest about that will lead to a different way of embarking on the person or the surrounding. There is a different depth to a statement like "What a beautiful body" after a process that includes being weirded out. Anne's story illustrated that rather than proclaiming tolerance and openness admitting irritation and judgement to oneself and others can open up a whole different dimension of insight and growth- if there is time and space to encounter that which is new and overwhelming. Be it a look, a person, a place, a feeling or a state. Oftentimes admitting these sensations requires trust. Not just trust in the process but also trust in yourself and your interlocutor. Again, because of a label: Being irritated is not cool. For who likes to admit they are weirded out at the sight of a penis that comes with a pair of boobs dangling above it, in 2015? Saying that out loud will cause at least one disgusted look, one "Go back to the fifties!" or one "You are an ignorant asshole!". But you are not. Admitting and walking through irritation, making use of the tools in your box like the male/female ruler, allowing yourself to do that, reminds me of WIttgenstein's ladder. The one you throw away after you have climbed it. Eventually you let the ladder go but you can't move upwards without the ladder. And you can't put the "male"/"female" ruler back into the toolbox unless you have picked it up before. Applying it does not mean claiming that its measurements, or any other of the toolbox's realities, equal the absolute truth. It does not mean going around and saying, "See, here she is female. Here she is male. And this part, aw well, hard to say. It kinda does not look human at all. Right?" But it means experiencing those thoughts awarely and allowing the thoughts to be (part of) your momentary truth. The same way that every new segment of a ladder you are climbing is your momentary truth. It means giving in to the process the way Anne did. Even if what you are experiencing seems wrong, bad, or evil. Be it thoughts, emotions, or ideas. And finally, it means trusting in that process even though you don't know what waits for you at the end.

I used to work for a professor who made a huge deal of being a feminist. At the same time he loved himself his hierarchies and made sure none of us female assistants questioned any of his claims and attitudes. But in theory he was a full on feminist. He would call in male staff to serve coffee at conferences so his guests would not assume he let women do the low skilled tasks (although all the secretaries and assistants at the institute were women while the people of high positions were men, without exception). That night, sipping bitter-sweet black tea by the sea with Anne, I thought of that former professor of mine. And I realized: I had learned more about feminism from Anne's life-drawing story about being real, even if that means going through "incorrect" stages, than from 1.5 years of working for the man with the polished feminist arguments.

I admire the way Anne gave in, allowed, trusted, and shared her experience with me. Her curiosity, acceptance and overall perspective were gifts to me. In the two weeks since we have met I have thought of her each time I felt irritated, and while I tried to immerse in the irritation it did not translate to my face because the memory of Anne occupied my mouth, causing my broadest smile.

The next morning, as I headed to the airport, I took pictures of the hills Anne and I had climbed on our way to the sea:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed